EMS was called to an office building for a 61-year-old male complaining of chest pain.

Just prior to EMS arrival the patient became nauseated and lightheaded. When they found him he was lying supine on the floor and appeared ashen.

- Onset: 45 minutes ago following a meeting with an important client

- Provoke: Nothing makes the pain better or worse

- Quality: “Squeezing”

- Radiate: The pain does not radiate to the arms, back, neck, or jaw

- Severity: 10/10

- Time: No previous episodes

He was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and event with a relatively calm demeanor.

Vital signs were assessed.

- RR: 24 (mildly labored)

- HR: 60 (weak radial pulses)

- NIBP: 87/40

- Temp: 98.4°F

- SpO2: 95% on room air

Breath sounds were clear bilaterally.

His medical history was remarkable only for hypertension and high cholesterol. He was unable to recall the names of his medications.

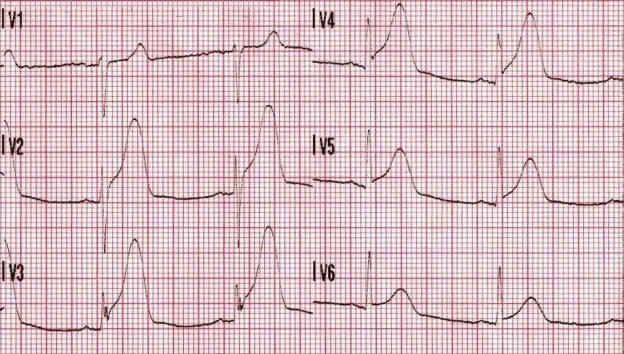

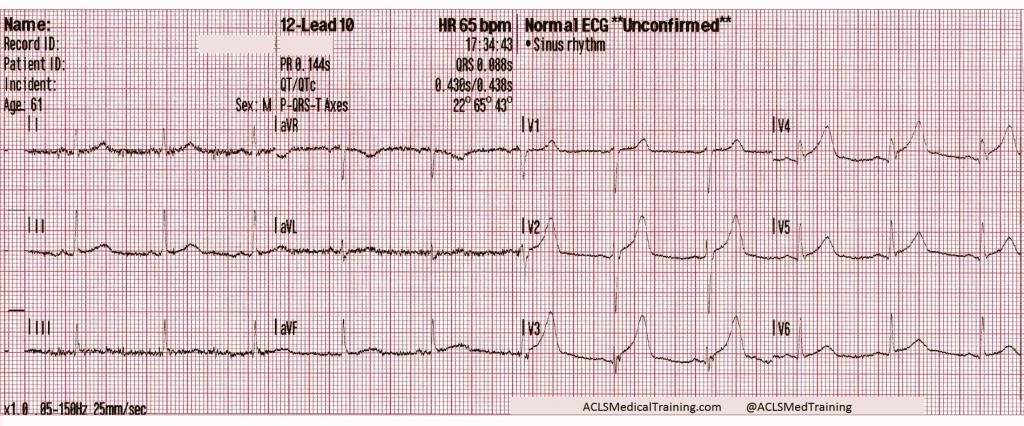

A 12-lead ECG was acquired.

ST-segment elevation is present in leads V2-V5 and the T-waves are hyperacute. It is unclear why the computer is not giving the *** MEETS ST ELEVATION MI CRITERIA *** message. This does not look like early repolarization or hyperkalemia.

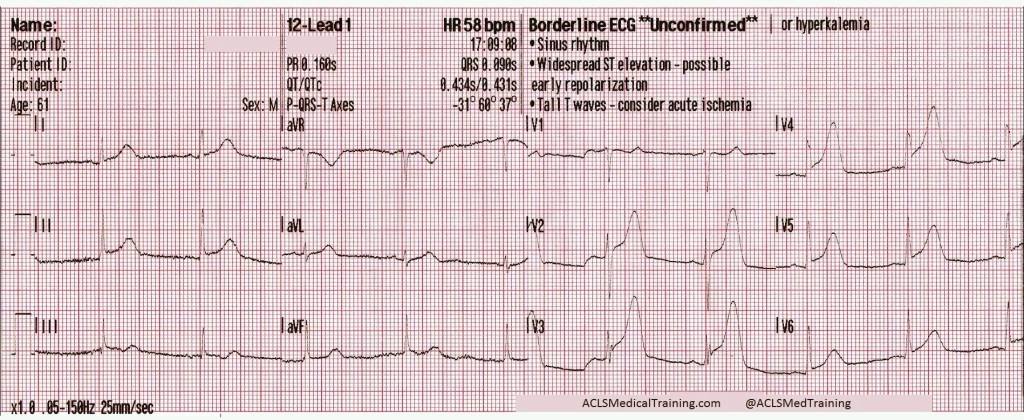

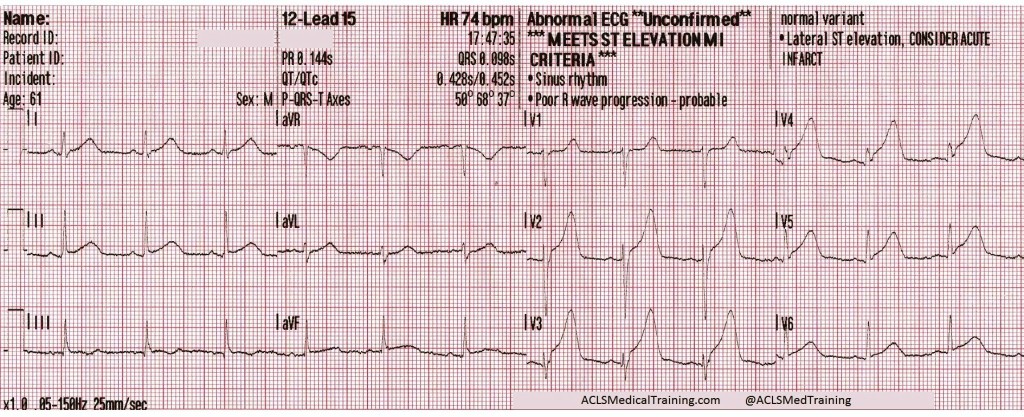

Then about two and a half minutes later…

We now have R-on-T PVCs, almost in bigeminy. The ST-segment elevation has resolved but the T-waves are still disproportionately large compared to the QRS complexes.

The treating paramedic correctly suspected that the patient was suffering an acute coronary syndrome, but there was uncertainty about whether or not it was a STEMI.

The patient was treated with aspirin and IV fluids for hypotension. The closest hospital was bypassed and the patient was transported to a PCI-hospital about 25 minutes away.

About 7 minutes later the patient’s blood pressure had improved to 102/69 but he was still complaining of 10/10 chest pain.

The ST-segment elevation has returned and the T-waves are unambiguously hyperacute. The computerized interpretive statement now reads *** MEETS ST ELEVATION MI CRITERIA ***

The ECG was transmitted to the hospital, IV fluids were continued, and 0.4 mg sublingual nitroglycerin was administered q 5min PRN, with moderate alleviation of the patient’s chest pain.

Vital signs were re-assessed.

- RR: 20

- HR: 64

- NIBP: 114/76

- SpO2: 98% on room air

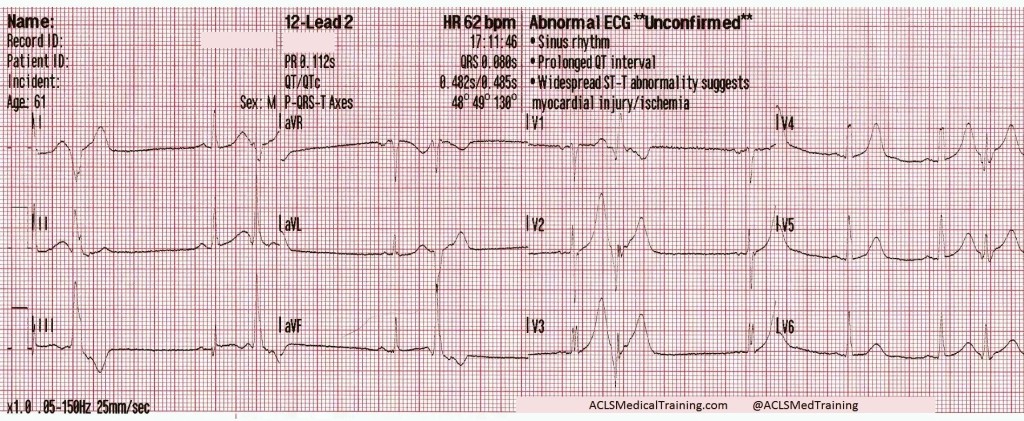

About fifteen minutes later this 12-lead ECG was acquired.

Once again the ST-segment elevation has resolved but there are still some troubling findings. R-wave progression has been obliterated and the T-waves are still disproportionately large when compared to the QRS complexes.

The ECG continued to show dynamic ST-segment and T-wave changes but they were mostly resolved by arrival at the hospital. The attending physician was waiting and there was some hesitation about sending the patient straight to the cardiac cath lab.

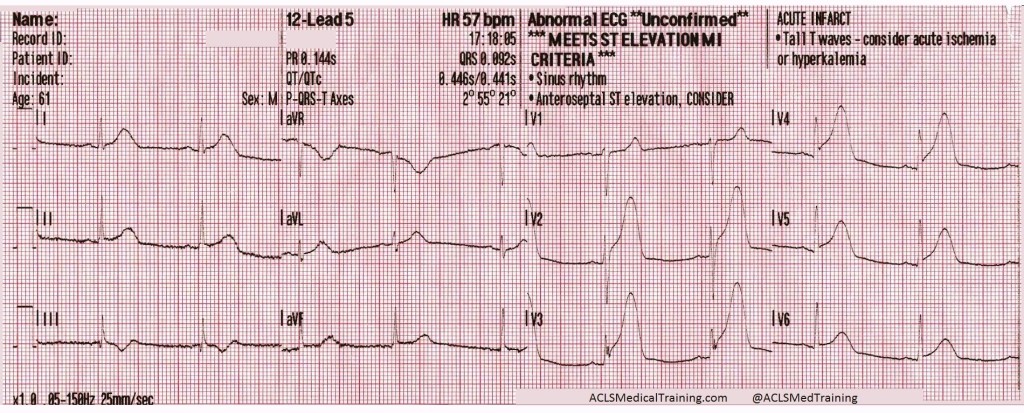

Before the patient could be moved from the paramedic’s stretcher the cardiac monitor automatically printed another 12-lead ECG.

The ST-segments and T-waves are back “on the way up” and once again the computer is giving the *** MEETS ST ELEVATION MI CRITERIA *** statement.

The cardiac cath lab was activated. Angiography revealed a 99% occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), which was stented.

Discussion Points

1.) Obtain a 12-lead ECG with the first set of vital signs!

Myocardial infarction is a dynamic disease process. Coronary arteries can become totally occluded, partially reperfused, and totally occluded again!

There are case reports demonstrating resolution of ST-segment elevation after administration of nitroglycerin.1 Stephen Smith, M.D. (@SmithECGBlog) writes about it here. Tom Bouthillet (@tbouthillet) writes about it here. Brooks Walsh, M.D (@BrooksWalsh) writes about it here and questions whether it’s really due to nitroglycerin here.

2.) Should transient STEMI be sent directly to the cardiac cath lab?

The short answer is probably.

This hasn’t been widely studied but there is literature to support early activation of the cardiac cath lab when dealing with transient STEMI. One study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine concluded that positive serial ECGs were more sensitive and more specific for identifying ACS patients who require anti-ischemic therapy, evaluation for reperfusion, and/or admission to an ICU.2

Articles in Prehospital Emergency Care and American Heart Journal show that while patients with transient STEMI were likely to have less myocardial damage, higher rates of thrombolysis, and better cardiac function, they still benefit from early invasive therapy.3,4

Check out this post from Stephen Smith, M.D. for an example of what can go wrong if you don’t send them for PCI!

3.) What is the significance of hyperacute T-waves?

T-waves corresponding with myocardial injury become taller, wider, and more symmetrical in morphology — a phenomenon referred to as “hyperacute T-waves”.

Hyperacute T-waves are the most reliable indicator of salvageable myocardium at risk!

Hyperacute T-waves are considered to be a STEMI equivalent even when the conventional mm criteria are not met. Look for these changes both as the ST segments are “on the way up” and “on the way down.”

4.) What’s the significance of those PVCs?

Patients suffering an acute myocardial infarction are at increased risk of developing lethal arrhythmias. Ischemic myocardium is “irritable” and the presence of PVCs may be a helpful prognostic indicator.

Proximity of PVCs to the preceding T-waves (“R-on-T” PVCs) present a greater risk that the patient will develop VT or VF as premature depolarization occurs during the relative-refractory period of the previous cardiac cycle.

5.) What is the significance of bradycardia in LAD/LCX occlusion?

This patient was unable to provide the names for his antihypertensive medication so it’s likely that he was prescribed a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker.

A less likely possibility is that there was ischemia of the SA node brought about by repeated occlusion/reperfusion of the circumflex artery.

This has been found in case reports and animal studies to cause transient episodes of sinus bradycardia, even though sinus bradycardia is more typical of acute inferior STEMI (RCA occlusion). 5,6

References

1) Mahoney BD, Hildebrandt DA, Allegra P. Normalization of Diagnostic For STEMI Prehospital ECG with Nitroglycerin Therapy. Prehospital Emergency Care 2008;15:105, Abstract 24

2) Fesmire FM. Usefulness of Automated Serial 12-Lead ECG Monitoring During the Initial Emergency Department Evaluation of Patients With Chest Pain. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31(1):3-11

3) Ownbey M. et al. Prevalence and interventional outcomes of patients with resolution of ST-segment elevation between prehospital and in-hospital ECG. Prehosp Emerg Care 18(2);174-9. Apr-Jun 2014

4) Meisel SR, et al. Transient ST-elevation myocardial infarction: clinical course with intense medical therapy and early invasive approach, and comparison with persistent ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 155(5):848

5) Lin, C.-F., & Cheng, S.-M. (2006). Symptomatic Bradycardia due to Total Occlusion of Left Circumflex Artery without Electrocardiographic Evidence of Myocardial Infarction at Initial Presentation. Texas Heart Institute Journal,33(3), 396–398.

6) William A. Alter, III, PH.D., Robert N. Hawkins, PH.D., and Delbert E. Evans. Etiology of the Negative Chronotropic Responses to Transient Coronary Artery Occlusion in the Anesthetized Rhesus Monkey. Circulation. 1978;57:756-762