This is the second post of a multi-part series reviewing the 2015 AHA ECC Guidelines.

Reference Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality

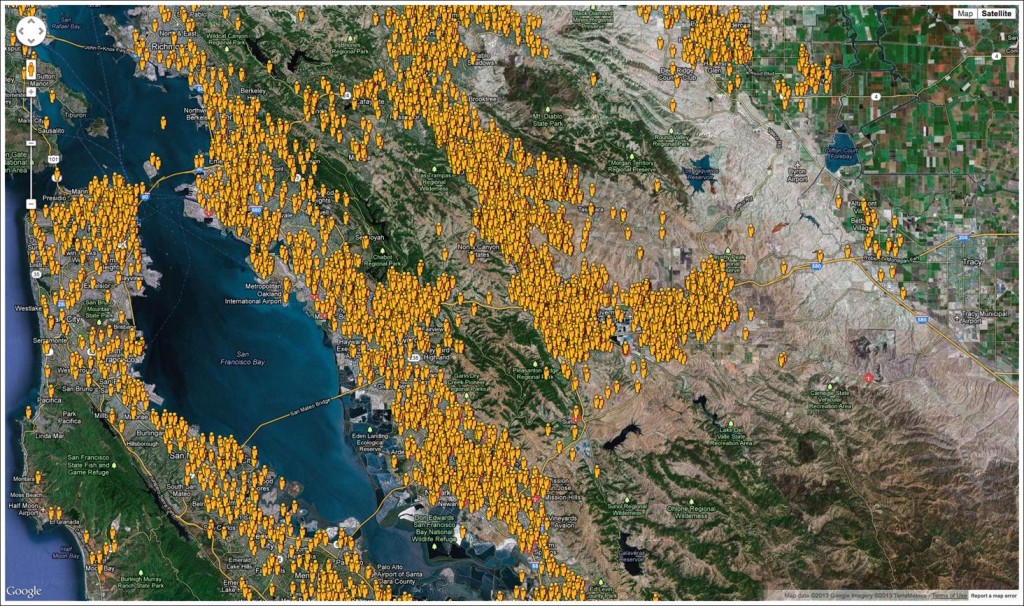

Epidemiology of sudden cardiac arrest

The guidelines make this sobering observation: 70% of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur in the home and 50% are unwitnessed. Only 10.8% of patients who receive resuscitative efforts by EMS survive to hospital discharge.

My department’s survival rate for unwitnessed cardiac arrest is 0% and I suspect that’s the case for the majority of EMS systems.

Basic life support is still the foundation of resuscitation

The chain-of-survival for out-of hospital cardiac arrest remains unchanged from 2010 with a few updates.

There is a greater emphasis on dispatcher recognition of sudden cardiac arrest with early CPR instructions (sometimes referred to as telephone CPR or T-CPR).

The guidelines reiterate the importance of high quality CPR.

- Ensuring adequate rate (100-120)

- Ensuring adequate depth (2 to 2.4” or 5 to 6 cm)

- Allowing full chest recoil (avoid leaning)

- Minimizing interruptions to chest compressions

- Avoiding excessive ventilation

This update recognizes the value of a highly choreographed approach that allows simultaneous approach to chest compressions, ventilations, airway management, rhythm detection, and shocking “by an integrated team of highly trained rescuers in appropriate settings.”

There is an acknowledgement that survival rates for witnessed VF can be as high as 50% in top performing EMS systems but vary from 5% to 50% — a 10 fold difference!

Clearly we would not accept this much variation in operative mortality.

Dispatcher recognition of cardiac arrest and CPR instructions

This may be one of the most important statements in the new guidelines:

“When dispatchers ask bystanders to determine if breathing is present, bystanders often misinterpret agonal gasps or abnormal breathing as normal breathing. This erroneous information can result in failure by dispatchers to identify potential cardiac arrest and failure to instruct bystanders to initiate CPR immediately. An important consideration is that brief, generalized seizures may be the first manifestation of cardiac arrest.”

Image credit: Wikipedia

Quality Improvement in the Dispatch Office

Performing QA/QI on the call intake process for sudden cardiac arrest is extremely important and it’s much harder than you may realize. It is doubtful that the QA/QI tools that come with Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD) software packages are adequate.

The CARES registry has an optional T-CPR module that measures various benchmarks for dispatcher performance including recognition of the need for CPR, how long it takes for the dispatcher to begin CPR instructions, and how long it takes for the bystander to begin compressions.

This represents a huge culture shift for dispatch and there is likely to be push back, especially if this type of monitoring occurs without appropriate training, or is implemented in a way that is punitive. However, it’s an often-neglected area of system performance.

As reported by the CARES Registry:

“One recent T-CPR initiative implemented guideline-based protocols, training, and feedback to staff at three regional dispatch centers. This “bundle of care” doubled the number of cases where bystanders started dispatch-directed compressions and reduced the time those compressions started by 80 seconds.”

That’s significant! This is simply not an area we can afford to ignore if we want to be good at resuscitation.

Do we want to be good at resuscitation?

If so, then these issues demand our time and attention. Once you’ve optimized on-scene performance (and hopefully realized some significant gains) you will plateau or perhaps even regress if you don’t find new opportunities to improve the chain-of-survival.

Updated recommendation for dispatchers

“It is recommended that emergency dispatchers determine if a patient is unresponsive with abnormal breathing after acquiring the requisite information to determine the location of the event. If the patient is unresponsive with abnormal or absent breathing, it is reasonable for the emergency dispatcher to assume that the patient is in cardiac arrest. Dispatchers should be educated to identify unresponsiveness with abnormal breathing and agonal gasps across a range of clinical presentations and descriptions.”

Will we pay attention to this recommendation?

I must admit that I find it a bit troubling that so many of my colleagues are saying “there’s nothing new in the 2015 guidelines.” This emphasis on the importance of the call intake process is critically important in my estimation and deserves to be taken seriously.

I hope I’m wrong but it almost reminds me of the 2000 AHA ECC Guidelines when it was first suggested that paramedics may not have enough experience to be proficient at tracheal intubation, and that alternate airways like the LMA might be more appropriate.

We simply did not like the message and many of us still don’t. We’re still arguing about it 15 years later although even the most stubborn of us have, at a minimum, admitted that tracheal intubation should not significantly interrupt chest compressions.

Anecdotally, having reviewed between 50 and 100 cardiac arrest calls using CODE-STAT for CPR analytics, it seems to me that most paramedics will not interrupt chest compressions for more than 10 or 15 seconds for the first attempt. However, if they miss the first attempt, all bets are off, and it is not uncommon for the second attempt to interrupt compressions for 15 to 30 seconds.

Because I know this tends to happen I have asked our paramedics to concentrate on expertly performed BLS for the first 5 cycles (10 minutes) of the cardiac arrest. A 30 second delay in chest compressions, while obviously not desirable, is more palatable at the 10 or 15-minute mark than during the “sweet spot” of the code.

I hope that many years from now (long after I am gone) others in our profession won’t look back and realize that we missed a huge opportunity to strengthen the chain-of-survival in our communities.

Again, I don’t suggest this will be easy. In fact, I’m certain it will be difficult. But with this recommendation it’s a good time to try.

Update: Click here to listen to Robert Lawrence interview Ben Bobrow, M.D. about dispatcher recognition of cardiac arrest and CPR instructions. Here’s the most important part:

“We have to look at this intervention as something we can quantify. So it’s not a binary thing. It’s not a yes or no…it’s not like a 9-1-1 system does this or they don’t, because almost every 9-1-1 system if you ask…answers that they do provide this life-saving service. But when you actually ask them how they train, what protocols they use, if they have a set protocol, how they measure it, what their performance standards are, it’s all over the board. So I think one of the main concepts, besides turning the public into an army of first responders, is that we need to measure, and have performance standards, for giving pre-arrival CPR instructions.”

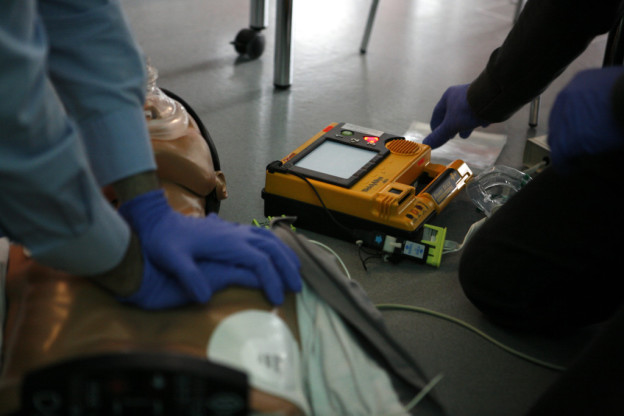

High Performance CPR training at EMS Today 2015

Consideration of the likely cause of the cardiac arrest

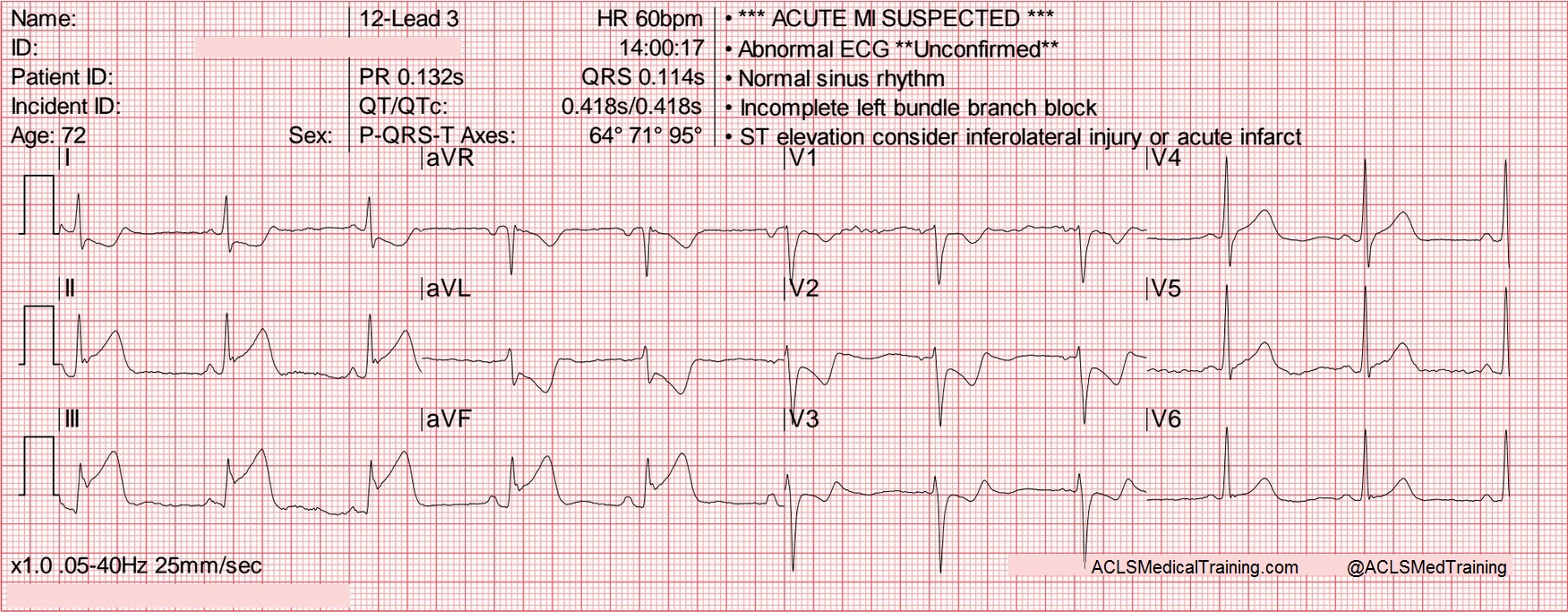

I personally found this update to be interesting:

“[I]t is realistic for healthcare providers to tailor the sequence of rescue actions to the most likely cause of arrest. For example, if a lone healthcare provider sees an adolescent suddenly collapse, the provider may assume that the victim has had a sudden arrhythmic arrest and call for help, get a nearby AED, return to the victim to use the AED, and then provide CPR.”

In my mind it is linked to the next issue.

Delayed positive pressure ventilation

Consider these recommendations:

“For witnessed OHCA with a shockable rhythm, it may be reasonable for EMS systems with priority-based, multitiered response to delay positive-pressure ventilation by using a strategy of up to 3 cycles of 200 continuous compressions with passive oxygen insufflation and airway adjuncts.”

And:

“We do not recommend the routine use of passive ventilation techniques during conventional CPR for adults. However, in EMS systems that use bundles of care involving continuous chest compressions, the use of passive ventilation techniques may be considered as part of that bundle.”

Setting aside the qualifiers (we could debate what it means to provide “priority-based, multitiered response” or to use “bundles of care”), the guidelines now acknowledge two important facts.

- Professional rescuers are capable of discerning between run-of-the-mill sudden cardiac arrest and asphyxial arrest which could potentially change how we approach the situation.

- Positive pressure ventilation is probably unnecessary during the first 6 minutes for witnessed VF/VT arrest.

This to me is a big change in the guidelines. Even though many EMS systems (including my own) have been using a form of Pit Crew CPR which is a hybrid between cardiocerebral resuscitation and 30:2, it’s nice to see the guidelines officially recognize the practice.

I have a suspicion that switching to continuous chest compressions with “passive oxygen insufflation” for the first 3 cycles (6 minutes or so) has the potential to save a lot of lives, especially in those EMS systems that have been waiting for the AHA to endorse the practice.

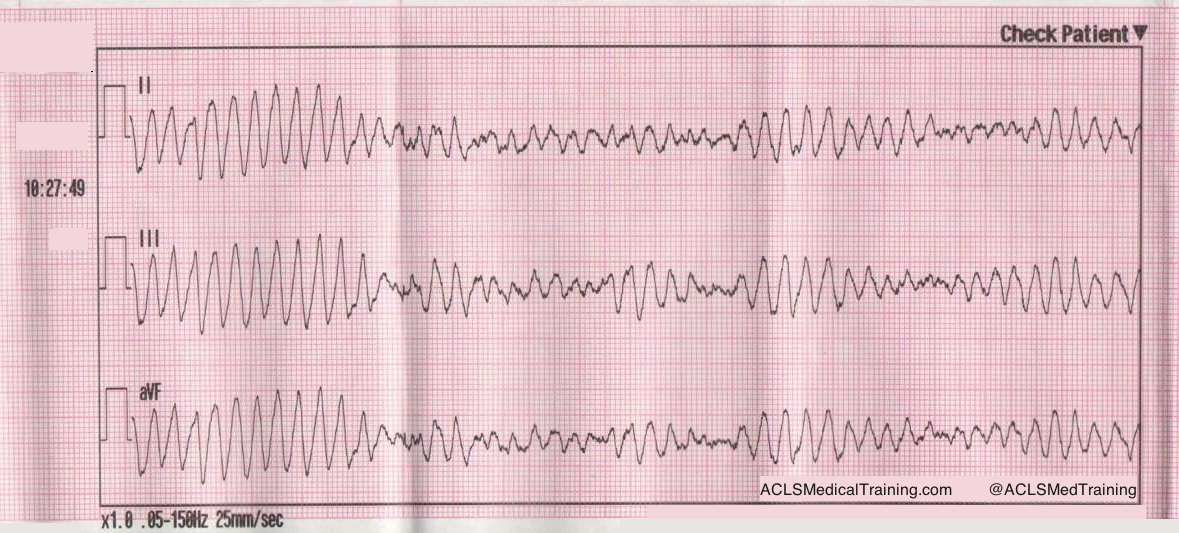

Rhythm checks and defibrillation

The guidelines reinforce that a defibrillator should be used as soon as possible and that chest compressions should be performed while the defibrillator is “being retrieved and applied.”

The evidence shows no survival benefit for a prescribed interval of 1.5 to 3 minutes of chest compressions prior to the first shock (when compared to a control group where chest compressions are performed while the defibrillator is being prepared).

However, I know from conducting time trials in my own department that it takes a good minute to turn on the defibrillator, extend the cables, attach the pads, apply the pads to the patient, charge the capacitor, and deliver the first shock.

So unless you’re by yourself there’s no reason the patient should not receive 100 chest compressions while all of this is happening.